By John Taylor, Amanda Minnaar and Steven Haggblade

Africa faces many critical challenges, chief among them raising the quality of its human resources, accelerating economic development and improving its peoples’ well-being. Food science and technology has a critical role to play in contributing to successful responses. Africa is changing rapidly and so are the challenges. Across the continent sustained economic growth now averages about 5% per annum. At the same time, the population continues to grow at roughly 3% per annum and is expected to double to 2 billion people by 2050. Even more startling, is the continent’s rapid urbanisation. According to UN Habitat by 2030 more than 50% of Africans will live in cities. As a result, Africa’s food consumption patterns will change dramatically over the coming decades. Urbanisation and growing per capita incomes will translate into greatly increased demand for processed foods, high-value foods (dairy, meat and fresh fruits and vegetables), packaged convenience foods and prepared foods. The agribusinesses emerging to meet this growing demand will require food scientists with expertise in modern food production and food safety technologies. At the same time, evidence strongly suggests that dietary changes and accompanying lifestyle changes are driving a rapid “Nutrition Transition”, leading to major health problems, involving an increase in obesity and its associated diseases.

Survey of Curricula in Africa:

A snapshot survey of food science and related curricula in 17 universities across 11 African countries revealed the following:

Fundamental problems:

Perceived challenges by food science and technology educators:

Nutrition Transition:

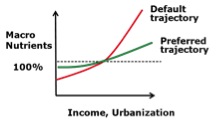

Although all countries in Africa continue to suffer from unacceptable levels of undernutrition, particularly among young children in rural areas, the rapid pace of the nutrition transition means that Africa increasingly faces the double burden of simultaneously high rates of under- and over-nutrition. South Africa has advanced quite far in its nutrition transition, from a predominantly rural population where people obtain most of their food through their own farming activities to an urban population purchasing its food from supermarkets, fast food outlets and street vendors. Other African countries are following close behind in this transition. Figure 1 below illustrates what happens to people’s macro- and micro-nutrient intake as populations go through the nutrition transition.

Across Africa, very disturbing health and disease consequences are accompanying this transition. A survey by GlaxoSmithKline in 2010 revealed that more than 60% of South Africans are overweight. Even in Tanzania, a low income country, a survey by Michigan State University of equal numbers of adult women involved in farming, housework and business, found that 49% were obese (mean BMI 30) and only 4% were chronically energy deficient (mean BMI 17.5). Research by the South African Medical Research Council showed that 15% of urban people in Africa have high blood pressure compared to 5% of the rural population. Today, in South Africa, some 25% of deaths result from cardiovascular disease and across Africa the incidence is 11%. The incidence of type 2 diabetes is also increasing rapidly in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Diabetes Leadership Forum in 2010 predicted that levels will double by 2040. Diabetes SA estimates that in South Africa 10% of the population have diabetes and most are unaware of their condition. A recent article in the Lancet revealed that in Tanzania, there has been a 3- to 7-fold increase in diabetes in the past 15 years to 6% of urban people.

Figure 1: Influence of urbanisation and rising incomes on macro- and micro-nutrient intake in developing countries (BCC Consortium)

Addressing Africa’s Food Science and Nutrition Education Challenges:

The Bending the Nutrition Transition Curve (BCC) Consortium, a consortium of African universities and institutes together with Michigan State University, is seeking to develop and help implement Africa-wide solutions to the challenges of nutrition transition in Africa. We have identified areas where food science and technology education has a critical role to play:

Development and implement common food science and technology curricula in Africa

This will facilitate:

Integrate nutrition and public health curricula with the food science and technology curricula:

Food industry entrepreneurship for high quality and indigenous foods:

The Role of IUFoST and IAFoST:

To fulfill the 2010 International Union of Food Science and Technology (IUFoST) Cape Town Declaration on Food Security, the active involvement of IUFoST and the food science and technology educators in Africa meet the continent’s multifaceted challenges. The following contributions will be critical:

Professors John Taylor (email: john.taylor@up.ac.za) and Amanda Minnaar are with the Department of Food Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa; Steven Haggblade is with the Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA

IUFoST Scientific Information Bulletin (SIB)

FOOD FRAUD PREVENTION