Albert EJ McGill

Background

In assuming the role of Editor-in-Chief of the journal Science in mid-2013, Marcia McNutt paid tribute to her predecessor, Bruce Alberts, and his work in promoting both the globalisation of science and its role as a platform on which to bring scientific disciplines together in addressing issues held in common (McNutt 2013). She also referred to the report of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences proposing a more active approach to breaking down the barriers across the science sectors establishing a “knowledge network” to tackle problems of common interest (American Academy of Arts and Science 2013). In a subsequent article on “Meeting Global Challenges”, Sharp and Leshner (2014) considered the multiple areas of Energy, Health, Water and Food and, while observing the need for converging approaches and the integration of knowledge from life, physical, social and economic sciences and engineering, concluded that neither science and technology funders nor performing institutions are well organised, nor are their members well trained for working in these ways.

In 2012 a project proposal was submitted to the International Council for Scientific Unions (ICSU) intended to bring together experts in various scientific disciplines from many international, regional and national unions and organisations dealing with weather, climate, disaster risk reduction, agriculture, food and sustainability. The proposal was entitled “Weather, Climate and Food Security (WeatCLiFS)” and intended to achieve its goals through the staging of symposia, a workshop and an open discussion forum. The proposal was supported by five ICSU Scientific Unions (the International Geographical Union - IGU, the International Union for Quaternary Science - INQUA, the International Union for Food Science and Technology - IUFoST, The International Union of Nutritional Sciences - IUNS and the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics - IUGG); the ICSU Disciplinary bodies; International Research on Disaster Risk (IRDR) and the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP); ICSU Regional Offices (the Regional Office for Africa - ROA, the Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific – ROAP, and the Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean – ROLAC); and Associate Partners the Asia Oceania Geosciences Society (AOGS) and the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP). While awaiting the outcome of the proposal for funding, four meetings were organised: a symposium as a session of the AGU meeting in Cancun, Mexico; a workshop in the Cameroons; a Workshop as a session of the AOGS Annual Meeting in Brisbane, Australia; and an Open Forum as a session of the IUNS Congress in Granada, Spain. Although this proposal was well supported, it failed to obtain funding and as a result many of the intended participants were unable to attend the meetings already organised. The initial intention was for IUFoST to be the lead organisation in this application but it was agreed that IUGG would take responsibility. As a result although all of the planned events took place, only IUGG, IUNS and IUFoST were able to support participation. This paper was the IUFoST contribution to the IUNS Congress in Granada and was thus orientated towards a nutrition theme.

Introduction

It was important at the outset to remind and inform the delegates to the Congress as to the role of IUFoST and also to define the fundamentals of food science and food technology, so as to show both the similarities and differences of our approach to the subject of food (or indeed nutrition) security even in the targeted urban context. A brief outline of the involvement of IUFoST in addressing food security was given highlighting both the Budapest Declaration of 1995 and its extension in Cape Town in 2010.

Food Security – Nutrition Security

It was important to point out that “the nutritional value of uneaten food is zero” and hence the supply of adequate food is a first priority of any nutritional context. The FAO (1996) definition of food security is a good place to start: “Food Security exists when all people, at all times, have access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preference for an active and healthy life.” Unfortunately, with the increasing popularity of the use, and misuse, of the food security terminology, there has been a tendency to ignore (or perhaps forget) key elements of the definition, in particular:

The exact position of communities on the continuum from death, dying, hungry, and malnourished to food insecure is seldom captured in published data and has undermined the policies of organisations like FAO and the World Food Programme (WFP). However, unless there is a delivery of edible food materials to consumers, wherever located, no adequate nutrition can be assured. Such deliveries are enabled by the supply chain.

Food Supply Chains

Although the processes may seem complex, they are based on some simple precepts and can be considered as follows:

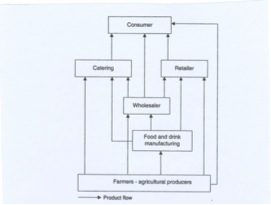

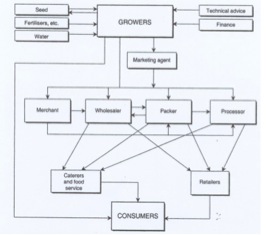

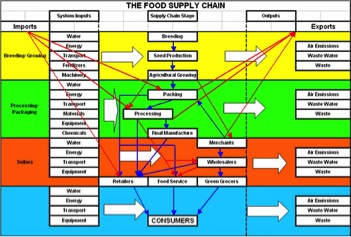

There remains a sense that supply chains are as linear as the name suggests even though the system is better considered as a network. Some examples are illustrated in Figures 1-3. As these supply networks become more complex and extend over greater distances so their success becomes more reliant on the security of each component and hence susceptible to interference from natural climactic events. Damage to infrastructures, roads, rail, air transport and power supply will delay or interrupt product delivery, posing both supply and food safety questions. At the urban level, transport disruptions resulting from adverse weather conditions, social protest, civil unrest and even armed conflict will prevent any access to food and damage nutritional status.

Climate Change and the Weather

Working with our colleagues at IUGG raises appreciation of the quantitative aspects of their profession. Geophysics involves, from its definition, “…the quantitative assessment of prevailing weather patterns, forecasting and recording unexpected climate change.” Although the most important consideration of accurate weather forecasting must be the information critical to farmers, the primary producers, any perusal of the dimensions and complexity of the food supply chain will indicate the importance of the same information in enabling such produce, in any form, to reach the consumer. Whatever the state of current debate on the anthropogenic causes of climate change, adverse weather conditions will disrupt not only the work of the farmer but also all the elements of the supply network, limiting the access to food for all consumers.

Figure 1. The UK food supply chain. Import/export activities are excluded.

(Taken from Bourlakis & Weightman 2014)

Figure 2. The UK Potato Supply Chain (Taken from Wilcockson, 2004)

Figure 3. The Food Supply Chain (Taken from Images of the Food Supply Chain,

www.google.com.au, 29/07/2014)

Discussion

It would seem inconceivable that anyone would try to improve the flow of water through a garden hose only by increasing pressure at the tap end, yet so much of what is published on food security is heavily weighted towards that process of ramping up production. Concentration on primary production is critical but relying only on e.g. doubling the level of production to feed growing populations seems to be relying on the ‘garden hose’ process. Some investigation of the reasons for failures of appropriate food delivery systems at the consumer end would seem to be justified.

More than half the world’s population currently live in cities and that proportion is growing and although there is frequently no shortage of adequate food that would constitute a healthy diet, the incidence of both obesity and undernutrition is of growing concern. The urban poor are often unable to access such a diet for economic reasons and because of lack of availability of fresh fruits and vegetables locally. There has been little indication of national government strategies to tackle these problems but a number of local community enterprises are making some impact. For example, the revival of the use of allotments in the UK, the Schrebergarten initiative in Germany, the Orgonoponicas activity in Cuba, the Daichi-o-Mamori-Kai partnership with consumers in Japan, and the initiatives emerging from the recent London Food Programme by local government. All these activities raise awareness and provide both food education and nutrition for all local residents and are making significant improvements to urban nutrition.

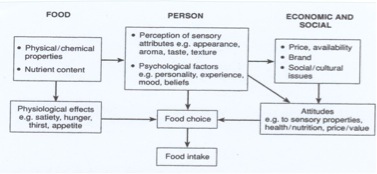

However, the impact of the effects of food preferences on food selection and the related nutritional status are difficult to quantify, particularly regarding cultural and religious practices, although these may be better dealt with at the community level. Factors affecting food choice are illustrated in Figure 4.

However, even at local levels, the effects of adverse weather through climate change will damage both produce and the infrastructures needed to allow distribution through the supply chain.

Figure 4. Factors affecting food choice and intake

(taken from Marshall 2004 and Shepherd 1989)

Conclusions

Global climate change is affecting and will continue to affect weather conditions critical for all aspects of agriculture and will change primary food production. Similarly, adverse weather condition can disrupt both the supply networks that provide our present access to food and its safety. Examples of food supply chains/networks are given in Figures 1-3 where the potential vulnerability of their infrastructure is evident.

For developing countries such impacts can destroy their staple crops and push their food security status into crisis. This will apply equally to urban as well as rural communities.

In developed countries the damage to infrastructure from adverse weather conditions may be less severe for some but will hit the urban poor disproportionately. Our reliance on ever expanding access to food materials in fuelling the consumers’ demands for all foods irrespective of the season has increased the risks associated with the loss of the associated complex supply networks.

The growth of some urban community projects are already reducing the reliance on extended food distribution networks through various forms of urban agriculture.

A better understanding of the effects of climate change on weather and hence on the production, processing and distribution of food indicate that initiatives such as the WeatCLiFS proposal are important in bringing together the expertise of professionals from the related disciplines.

Postscript

At the First Workshop of the IUGG Commission on Climatic and Environmental Change (CCEC) held in Beijing, China, 11-12 April 2014, the remaining participants of the WeatCLiFS consortium (IUGG, IUFoST and IUNS) were asked to focus on the hazards-disaster-food nexus and examine the question: What technologies and methodologies are required to assess the vulnerability of people and places to hazards [such as famine] – and how might these be applied on a variety of spatial and temporal scales?

This is appropriate as one of the existing Future Earth activities is CCAFS – Climate Change and Food Security. A poster summarising the achievements of WeatCLiFS, so far without ICSU support, was presented to the ICSU General Assembly by Dr Tom Beer of IUGG (who has promoted the WeatCLifs consortium energetically from its inception) in Auckland on 2 September 2014. His short presentation was well received and subsequently the Chair of the Session encouraged an application for funding through the Fast Track Initiative for the ICSU Future Earth Research Programme.

References

American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2013). ARISE 2: Unleashing America’s Research and Innovation Enterprise, available at: www.amacad.org/arise2.pdf ,p.xiii.

Bourkalis, MA and Weightman, PWH (2004) Introduction to the UK Food Supply Chain, Figure 1.1, page 6. In Bourkalis, MA and Weightman, PWH (eds) Food Supply Chain Management. London: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; ISBN 1-4051-0168-7.

Marshall, D (2004) The Food Consumer and the Supply Chain, Figure 2.2, page 21. In Bourkalis, MA and Weightman, PWH (eds) Food Supply Chain Management. Londonm: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; ISBN 1-4051-0168-7.

McNutt, M (2013) Passing the Baton. Science 340: 1141.

Sharp, PA and Leshner, AI (2014) Meeting Global Challenges. Science 343: 579.

Wilcockson, S (2004) UK Crop Production, Figure 6.1, page 90. In Bourkalis, MA and Weightman, PWH (eds) Food Supply Chain Management. London: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; ISBN 1- 4051-0168-7.

Dr Albert McGill has been a Visiting Professor at the National University of Singapore and The University of Fuzhou, PRC, and a Visiting Fellow at the James Martin Institute for Science and Civilisation at Oxford University, UK. He is a former Dean of Science, Engineering and Technology at Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia, and is a member of the Food Security Task Force with the International Union of Food Science and Technology (IUFoST) having specific responsibility for Emergency Feeding Systems as part of the Disaster Relief Initiative; 89 Melvins Road, Riddells Creek, Victoria 3431, Australia, email: albert.mcgill@futureforfood.com

IUFoST Scientific Information Bulletin (SIB)

FOOD FRAUD PREVENTION