L. L. Daisy, A. K. Faraj, J. M. Matofari

Abstract

With the increased production of mango fruits, it becomes necessary for the farmers to improvise ways on how they should process and preserve the mangoes during that particular time of the year when their production is at their maximum. This is because, first and foremost, mangoes are perishable, they undergo spoilage days after their harvest. Second, mango fruits are not produced throughout the year as they are seasonal. With appropriate processing and preservation methods, it becomes possible for mangoes to be kept for longer period and.to be available during those periods when there is no production. It is hence important to get a good understanding of the processing and preservation process involved within the mango value chain in order to help curb the process of food losses through spoilage.

Introduction

Mango (Mangifera indica) of the family Ancardiaceae is a tropical, subtropical and frost-free fruit. It is the fifth largest fruit crop produced worldwide after banana, grapes, apples and oranges. It is the second most important tropical fruit with 27 million tons being produced annually worldwide (Bally et al., 2009). It originated from the foothills of the Himalayas of India and Burma and has been cultivated in that region for at least 4,000 years.

In Kenya, mango has been the third most important fruit in terms of area and total production after bananas, including plantains, and pineapples for the last ten years (HCDA 2010). The hectares under mango production, production output (ton) and the revenue earned have continued increasing over the years. Hectarage increased from 36,304Ha to 59,260Ha; production from 528,815 MT to 636,585 MT and revenue earned increased from $US 104.6 to $US139.8 (HCDA 2011). It has been cultivated in the Coast Province for centuries. It was first introduced into the country by ivory and slave traders who brought seed during the 14th century. Since then it has spread to most parts of the country including Eastern, Central, North Eastern, Western and South Nyanza Provinces (Griesbach 2003).

Postharvest losses of mango fruits in Kenya are estimated to be 40-50% through the market value chain to consumption and less than 1% is processed to value added products (FAO 2006).

Value addition of mango fruit to curb high losses, may be utilised to offer high priced products and alleviate poverty through enhanced food and nutrition security. This is in terms of quantity, quality, safety, and variety (Abe et al. 1997). This can be done by using applicable postharvest technologies which preserves the fruits’ qualities. This include practices like hand harvesting, refrigerated transportation tracks, proper cleaning, cooling / refrigerated storage, drying, packaging and labelling, pulp extraction, preservation and processing to various products like juices, jams, concentrates, nectars, powders and slices. The value-added products offer higher return, open new markets, create brand recognition, and add variety to a farm operation (Bachmann 2001).

Mango Varieties in Kenya

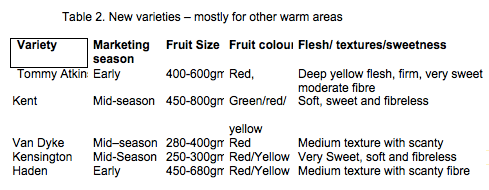

Two types of mangoes are grown in Kenya: the local, and the exotic or improved varieties. The local varieties include Ngowe, Dodo, Boribo and Batawi. The exotic varieties include the Apples, Kent, Keit, Tommy Atkins, Van Dyke, Haden, Sensation, Sabre, Sabine, Pafin, Maya, Kenstone and Gesine. The exotic varieties are usually grafted on local mangoes. They are of superior qualities with higher juice yields and are often grown targeting the export market. Recommended varieties are shown in Table 1and new varieties in Table 2.

Preferred varieties for export are Ngowe, Apple, Kent and Boribo. In most cases Tommy Atkins has a long shelf life, is resistant to anthracnose and powdery mildews; Ngowe is susceptible to powdery mildews; Haden can be used as rootstock because of its good quality, medium to large size, is very juicy and has a pleasant aroma. Kent is late maturing, while Apple is susceptible to anthracnose and powdery mildews.

Most local varieties tend to have high fibre content, commonly referred to as “stringy” and thus are less preferred for fresh, processing and export markets. They are relatively cheap compared to the exotic varieties and require less attention in their growing.

This great diversity of mango fruit types permits considerable manipulation for various purposes and markets: juice, chutney, pickles, jam/jelly, fresh fruit, canned and/or dried fruit. Given the multiple products, it is therefore a potential source of foreign exchange for a developing country, a source of employment for a considerable seasonal labour force and also, a source of nutrients for the human population.

Mango Value Chain

A value chain outlines the physical flow of production and commercialisation and the enabling national and international institutional environment needed for an effective value chain development. Value chains provide potential benefits for both rural producers and urban consumers. They also act as a supply chain – whereby the actors know each other well and form stable, long-term relationships, supporting each other so they can together increase their efficiency and competitiveness. They invest time, effort and money to reach a common goal of satisfying consumer needs hence enabling them to increase their profits.

Value chains provide potential benefits for both rural producers and urban consumers. Producers receive particular attention, as they are perhaps the most apparent manifestation of the value chain. Receiving less attention, but of equal importance, are traders. We are all part of a supply chain: as consumers, we buy mangoes from a retailer, who gets them from a wholesaler, who buys them from a trader, who gets them from a producer.

Servicing the supply chain itself is a multitude of other players: those providing transport, processing, finance, packaging, quality control, book keeping, among others services. There are also governments and private agencies that provide information on prices and quantities, which set the rules governing the market, for example.

At each stage in the chain the price of the product goes up. That is because each actor in the chain adds to its value – by growing, harvesting, sorting, grading, packaging, processing, labelling, transporting, storing, and putting it on shelves for us to buy. Each of these steps costs money, which the actor recoups by charging for the service (KIT and IIRR 2008).

Mango Processing

The great diversity of mango fruit types permits its use for various purposes and markets. Mango processing entails the transformation of mango fruits into different semi-finished and or ready-to use products. Such products include: juices, jam, jelly, nectar, concentrates and wine. Mangoes can also be used as a salad component, a salad appetiser, pickles, candied mango pulp, ice cream component, mango scoops or tidbit, mango shake and chutney.

In Kenya, mango juice is the most common product. The fruit is first pulped into a concentrate and then made into mango juice. Processors include Kevian Kenya Ltd., which sells juice under the trade name of “Pick and Peel”, and Sunny Processors, that produce mainly pulp, exporting the majority (Sunny Processors, 2010), and others such as Milly and Truefoods. These processors are located in and around large towns such as Nairobi, Thika and Mombasa. Some processors, e.g. Del Monte, import the concentrate from outside Kenya and then convert it into juice for the Kenyan market. The juices are packaged in Tetra Pak carton packages and plastic bottles and sold locally.

Coca-Cola has introduced a plan to locally procure mangoes with a view to producing soft drinks in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Techno-Serve, who will provide farmer organisation, technical and business services (Njiraini, 2001). However, there are doubts about the future competitiveness of local production for juice. First and foremost, fruit juice production requires large scale, low cost production. Second, processing of the mango fruit presents many challenges as far as industrialisation and market expansion is concerned. These challenges include:

· Trees are alternate bearing, and the fruit is only available for about seven months in a year. The crop is bulky and has a short storage life, thereby making it difficult to process in a continuous and regular way.

· A large number of varieties with their individual properties affect the quality and uniformity of processed products.

· Interested entrepreneurs may not know where to get the processing equipment and better linkages need to be created between the technology providers and users.

· Those investing in mango production may not have the necessary processing skills and may not employ qualified personnel as they may consider them too expensive to hire.

· Mango processing in Kenya also faces competition from cheap imitation fruit drinks and imported fruit juices and concentrates, as well as from other products.

· The majority of Kenyan consumers may not be aware of nutritional and health benefits of consuming mango products or other natural fruit products as compared to synthetic or imitation products (KIRDI 2009, KEVIAN 2010).

Mango quality required in processing should possess the following characteristics:

· have no blemishes, bruises (mechanical damage and diseased mangoes);

· have a good size, appearance, taste and flavour;

· should be firm fruit;

· should have a good texture and low fibre content;

· desired processing ripeness;

· physiologically mature fruit;

· high sugar totacid ratio;

· should have an attractive pulp colour, and

· high recovery rate during processing.

The above characteristics are influenced by the following:

· variety of the mango;

· pre-harvest technologies;

· postharvest handling (food safety) (Chege, KARI).

· processors often acquire the bulk of mangoes directly through brokers and at a

small scale from the producers (FAO nd, Team interviews 2010).

Reasons for Mango Processing

There are various reasons as to why mangoes are always processed. Some of these reasons include:

· to decrease postharvest losses and extend shelf life;

· to create variety and hence widen the market;

· to add value, thereby generating extra income;

· to create new investment and employment opportunities;

· to improve the nutritional quality of mangoes e.g. through pickling;

· to support local small-scale industry through the demand for equipment required for

processing, preservation and packaging (KIRDI, 2009).

Mango Preservation

Food preservation refers to any one of a number of techniques used to prevent food from spoiling. It includes methods such as canning, pickling, drying and freeze-drying, irradiation, pasteurisation, smoking, and the addition of chemical additives. It is aimed at extending the shelf life of a particular food. Mango preservation is a very crucial process since the fruits are perishable, hence they cannot keep for long. Various methods are employed to effect the preservation process, some of these methods are as discussed below.

Blanching

This is an example of a hot-water treatment method. This operation is done to inactivate enzymes, eliminate air inside the fruit tissues, remove off-flavours and aromas, fix fruit colour and soften the tissues. Two methods are currently used to effect blanching: dip in boiling water or direct steam injection. The thermal treatment is applied such that internal fruit temperature reaches 75°C. This usually requires 10 minutes in boiling water, or 6 minutes with steam. Fruit is blanched unpeeled. The effectiveness of the blanching treatment is usually determined by measuring the residual activity of an enzyme called peroxidase.

Sulphiting

This is a process which involves dipping the mango fruits in a solution of metabisulphite (200 mg/L). It is aimed at preventing undesirable colour changes of the mangoes. It also helps in preventing additional microbial and enzyme activity and retains a residual concentration of about 100 mg/L in the final product.

Canning

This is a method of preserving food in which the food contents are processed and sealed in an airtight container. Canning provides a shelf life typically ranging from one to five years, although under specific circumstances it can be much longer. In this process, heat sufficient to destroy spoilage microorganisms is applied to mango slices packed into sealed or "airtight" containers. The slices are then heated under steam pressure at temperatures of 116-121° C.. In most cases, the amount of time needed for processing is different for various fruits, depending on the food's acidity, density and ability to transfer heat.

Pickling

This is a process of preserving or expanding the lifespan of food by either anaerobic fermentation in brine or immersion in vinegar. The resulting food is called a pickle. In this process, the jar and lid are first boiled in order to sterilise them. The fruits to be pickled are then added to the jar along with brine, vinegar, or both, as well as spices, and are then allowed to ferment until the desired taste is obtained. The mango fruit can be pre-soaked in brine before transferring to vinegar. This reduces the water content of the fruit which would otherwise dilute the vinegar.

Freezing

This is a process aimed at subjecting the mangoes to very cold storage conditions. In this case, equipment such as refrigerators are used. When mangoes are purposed to be stored for a year, freezing of the fresh and ripened mangoes is the best method. Mangoes of the same ripening stage are obtained; their skins are then peeled off, then cut into small pieces and the seeds removed from them. The cut slices are then placed in the zip lock freezer bags, which are then zipped and wrapped in aluminium foil. After this, they are stored in the freezer (ideally at -10oC or below) for a period of up to one year.

Mango Preserve

This is a traditional method of preserving mangoes that are like jam and can be used as spreads. In this case, the mangoes are peeled off their skin and made into thick slices in a broad bottomed vessel. The mango juice is collected during the cutting process. Sugar is then added to the vessel containing the slices and juice in the ratio 1:1 and then allowed to set for a few minutes. The sugar is stirred while the mixture is kept on high flame and cooked until the entire ingredients begin to boil. This is done until a golden yellow and thick texture is reached. Citric acid (1 g) is added until a desired sour taste is reached. A half tea spoon of metabisulphite is added and the mixture mixed together. This could be made as a juicy paste, syrup or hardened to slices. They can also be bottled for future use.

Drying

This is one of the oldest methods of food preservation, which reduces water activity sufficiently to delay or prevent microbial (yeast and/or mould) growth. Loss of moisture content produced by drying, results in increased concentration of nutrients in the remaining fruit mass. Control of bacterial contaminants in dried foods requires high-quality raw materials having low contamination, adequate sanitation in the processing plant, pasteurisation before drying and good storage conditions.

Modified atmosphere (controlled atmosphere)

Controlled atmosphere (CA) storage usually involves regulating the concentration of oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) using nitrogen, storage temperature, as well as relative humidity in the storage environment. CA in combination with an optimum storage temperature has been reported to prolong the storage life and maintain fruit quality including aroma volatiles in mango fruit depending upon the cultivar. Fruit quality is an important factor in influencing consumer preferences in international and domestic markets.

Challenges Facing Mango Farming in Kenya

The main challenges facing mango farming as a business in Kenya includes;

· poor farm management,

· improper harvesting and post harvesting handling,

· lack of refrigerated transportation and storage facility at both the farm and market places.

· minimal value addition technologies

· lack of viable markets of the fresh fruit, and

· high competition of the processed mango products from artificial juices and imported juices

Conclusions

Mango farming should be handled with all the seriousness it deserves and all the activities within the value chain be conducted efficiently. This will help reduce losses due to deterioration and encourage the production of high quality products. This will in turn help in ensuring that the availability of mangoes is positive throughout the year. Also, it will help in boosting the economy due to the sale of the varied mango products produced during the processing period.

References

Bachmann. J, (2001). Adding value to farm produce: An overview. Appropriate Technology

Bally, I., Lu P. and Johnson, (2009). Mango breeding in Jain, S.M and Priyadarshan P.M

(eds), Breeding plantation tree \crops: Tropical Species Springer Science; Business

Media.

Chegeh, B.K. (2010) Value Chain Concept in Mango Production in Kenya, KARI-Thika: A

presentation during a local stakeholders’ meeting on Mango Value Chain in Mbeere held on 30/03/2010, held at KARI-Embu.

FAO (2001). The world trade in mangoes and mango products and opportunities for Kenya

partnerships for food industry development - fruits and vegetables (PFID-FV).

http://www.allaboutmangoes.com/mango%20production/MangoKenya.pdf

FAO (n.d.) Value chain analysis: a case study of mangoes in Kenya. Food and Agriculture

Organization, Rome. 11 pp.

Griesbach, J. (2003) Mango growing in Kenya. World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), Nairobi

Kenya, 117 pp.

KIT and IIRR (2008) Trading up: Building cooperation between farmers and traders in Africa.

Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam; and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi.

Njiraini, J. (2010) Coca-Cola To Incorporate Farmers Into Supply Chain

Mediahouse: East African Standard.

http://www.marsgroupkenya.org/multimedia/?StoryID=278195

Sunny Processors (2010) http://www.alibaba.com/member/sunmango/aboutus.html

L. L. Daisy (corresponding author, e-mail: daisy.lanoi@gmail.com), A K Faraj and J M Matofari are with the Department of Food Science and Technology, Egerton University, PO Box 536-20115, Egerton, Kenya

IUFoST Scientific Information Bulletin (SIB)

FOOD FRAUD PREVENTION